What is life? Is it a passive thing, active, free, determined, absurd, rich? Clearly I’m not going to try and answer all that, perhaps any of that, nor am I close to qualified to, but they are questions, nonetheless, that need to be asked in the run of a life.

By the way, it is good to talk again. Sorry for the absence, but with a full heart I report that my wife and I have been traveling to mark our 10th year wedding anniversary. We’ve been in Paris, Athens, and a little Aegean island named Naxos. But this isn’t a travel article, so back to our question.

One of the things I had fun doing on this trip was taking along books that were roughly themed to the places we were going. This led me to read Albert Camus’ The Stranger in Paris. Camus worked and lived in Paris for some time, though the book is about a French colony in North Africa. More on that book in just a moment. But right now I want to talk about birds. Now I know this is more jumping around than we normally do, but this is a quick letter to you, after all.

Birds. I had never encountered something like Versailles in my life, I guess few do. Nor had I ever been to a palace of any kind—for some reason they are in short supply where I grew up. But one day, with the right tickets purchased, we walked around one of the most opulent properties in the world. Glimmering gold and looking like some great piece of jewelry rising from the ground. The irony was clear, however, for the price of a lunch, mere everyday folk could walk golden halls and gilded chambers where no royalty dwelled any longer—it was now a palace for the people, that was the theme of the French phrasing on the placards outside the buildings. The striking abundance, and, emptiness of the former residence was surreal.

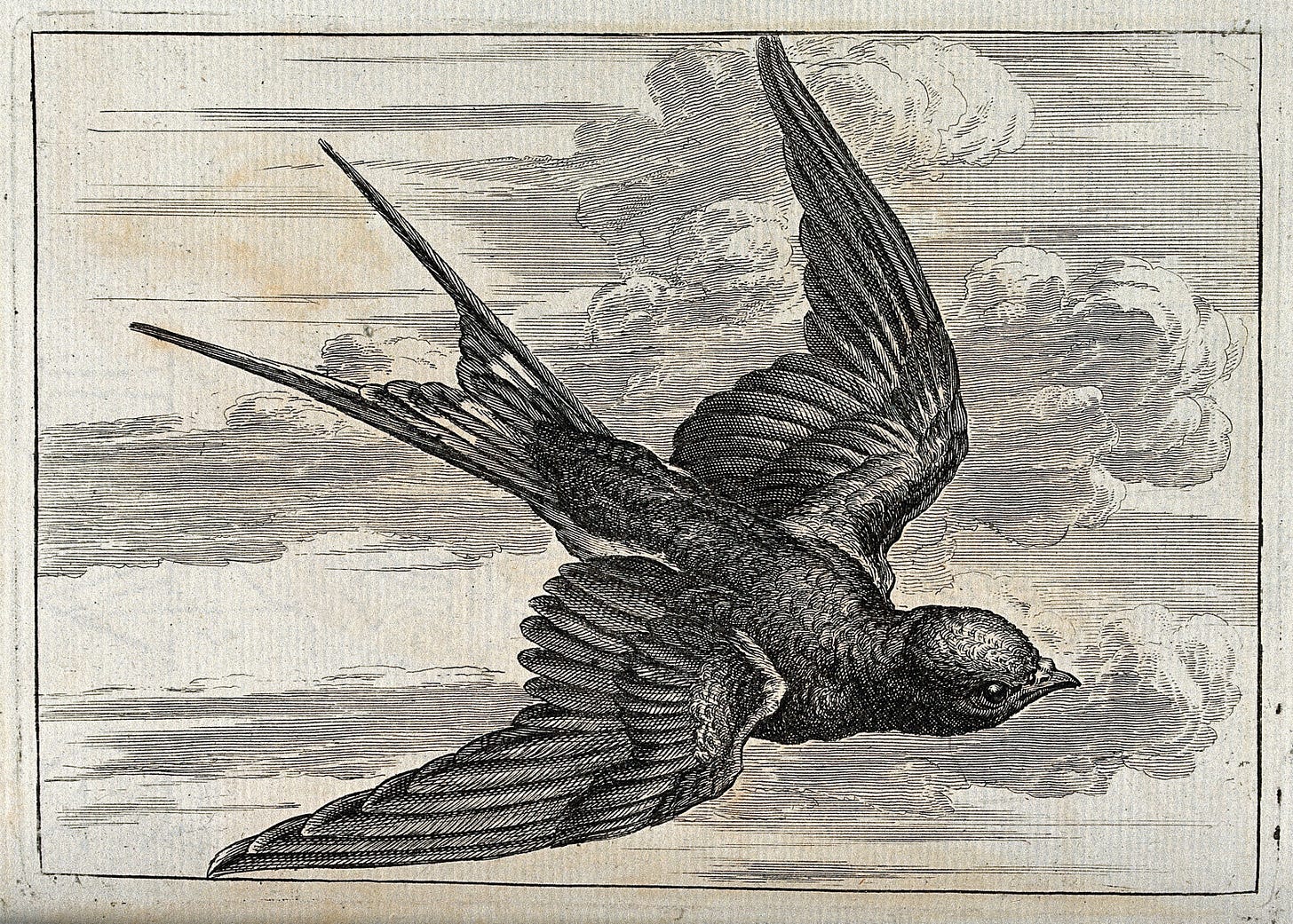

The buildings themselves were impressive, as were the gardens, and after hours of walking we needed a break. A break from both palace and people. So my wife and I found a quiet corner of the gardens with a view of the grounds and façade and just sat there. And after a while, above us we noticed something we had glanced through the windows of the king’s chambers. Over the palace danced and undulated the form of a mass of swallows in flight. The little birds twisting and sweeping along the lines of the property.

It was a sight we would witness again on a different day of the trip, in a very different place to Versailles. We saw another flock of those busy artisans as we topped the hill of the Athenian acropolis one morning. Even though it was dawn, the heat was punishing, and so there on the mount we found a quick rest in the shade, only to notice a group of swallows spinning their flighted forms above us.

And it occurs to a person, looking up and looking down, grandeur and sky, do these little birds have any conception of what they are flying above, or amongst? Don’t they know they fly amidst glorious houses, vaults of riches, seedbeds of ideas, and places of power? They are unbothered. They are born, they live, and they die in places that we have adorned with importance and yet they live simply with no care for it, going about their days. Camus might say that is because life itself is absurd, and what the birds are doing is simply pointing out the absurdity of it, and of us. That two different species are born, live, and die—one building palaces, speaking dreams in grand oration, while the other makes humble nests and cares not for golden endeavors, and it just shows it’s all nonsense. For both end up similarly in death after all….Absurd.

However, even though I empathize at times with Camus’ absurdism. I much prefer Kierkegaard’s movement of the soul. But perhaps we should sketch out a three-step progression to get from Camus to Kierkegaard to explain what I mean. Progression 1: we become aware of the absurdity of life (this step seems shared by both men). This is something we all need to do. There should be a part within us that looks upon life—with its love, dreams, hopes, longings, talents, and joys—and then looks down on death and sees it for what it is: utterly absurd. Absurd, yet it is the thing that all humans will share in common. It foreshortens and stifles all of those things we hold dear—at the end of life, of course—but also during it, during those moments when we see the end of something we thought might last or grow or succeed a bit more.

Death is absurd, and so for an absurdist, it makes whatever precedes it so as well, to varying degrees. If Progression 1 is all there is, then it is all there is, and a bleak outlook.

Yet, if we follow the progression up, it is here we depart from Camus and enter Progression 2: the territory of the Preacher (the Kohelet) from Ecclesiastes. It is here that we again find awareness of the absurdity of life, and that all is vapor under the sun. That life is short, and things will decay. But it is here, with the Preacher, that we begin the movement, from absurdity alone, to something greater. It is here with the Preacher that we see that absurdity is in fact alienation.

And so the Preacher gives us awareness of this absurdity plus one more thing—hope. Hope, that great hinge upon which the whole world turns—and us with it.

Hope—that injustice will one day see justice. Hope—that one day the frustration of love, of joy, and of peace—that frustration—will be taken off of them. Hope—that in the end, it all really did matter, both the hardest parts, and highest points. Hope—that there is something very great in the world, the greatest thing in fact, higher than the world itself, and it is mindful of us. Something so great that we had not even dared to imagine it fully. And that stronger than this absurdity, all along there was love. Hope, that we weren’t just an absurd species in an absurd universe after all. The Preacher has gestured to the door that opens out from the absurd.

This then brings us to Progression 3, and to something Kierkegaard explored. The movement of the soul from absurdity, to an awareness of alienation, and finally, the last stage, to an encountering of God, and in so encountering Him, the end of the absurdity of alienation. It is this movement that can take the pains of life and give them patient hope, until at last one day the very pains themselves will find restoration.

It comes with a hope so thick, so potent, so profound that you don’t even need to be like those great royals in palaces or like those wise orators in the halls of the acropolis, agora, or stoa to be hopeful. In fact, far from that greatness, you may be even as lowly as one of the birds flying above them all. And though through history we have sought the palaces and forgot the paupers, this grandeur was a false safety from absurdity. There is something far simpler, and far more beautiful than all that. It’s found in a sermon.

“Look at the birds of the air: they neither sow nor reap nor gather into barns, and yet your heavenly Father feeds them. Are you not of more value than they?“ —Matthew 6.26

And so it is this hope of love, and that there is a God who is mindful of us, that is the final end of absurdity, and that whether we be gilded in gold or in rags, in the end, it is the movement that is everything. It is the movement that goes to work on our question. And so the birds serve not as a reminder of this absurdity, but this hope.

“Therefore do not be anxious about tomorrow”

—Matthew 6.34

“his is the kingdom and the power and the glory forever; then there is for you a ‘today’ that never ends”

—Søren Kierkegaard