There are so many experts around these days, it is hard to get a word in. Just now, on the way to write this I ran into a herd of them. Hot tips about this and that and everything in between. Lucky for you I am no expert, so take a breath, this isn’t that kind of place. But maybe you and I are similar, just interested in stories, learners of a different sort, that’s a lot more interesting anyway. Popularly, I see that what a person is best qualified to talk about these days is directly connected to what makes them their money, and so this might be the only topic I am actually qualified to write about—creativity. I am not a very great creative, as the world looks for influencers, the famous, or the wealthy. But I have satisfaction telling you that I have made learning creativity an important part of my life, and if it makes a person feel better, I have made a living from creativity for about a decade, and so that will have to be enough.

I wanted to put together some thoughts concerning what I’ve learned along the way, both to act as a little insight, and also as an encouragement. And if you are reading this out of bordem, maybe it’ll pass some time. This is for three kinds of people: for those who are creative-types and work with those skills, for those who wish they did, and for those who are just curious. I’ll split this chat into a few sections.

The Creative Club

I think the first thing I want to say is that there are creative people, and then there are people who just aren’t. Well, at least that’s the feeling you get if you hang out with some ‘creatives,’ but it isn’t right, in fact I think it’s pretty wrong. In reality, I have a different saying, it’s this: everyone is creative. Now, you might be thinking that this is generous, especially considering that one person you sometimes talk to at work parties, you know who I mean—but I really believe it is true. There aren’t just some people who are ‘creatives’ or whatever you want to call them, and then there are normal, regular people, that’s ridiculous. In fact, it is so ridiculous it runs counter to what defines humanity. For the non-Christian we can at least agree that humans have been making things—tools, language, art, culture—since we arose as a species. And for the Christian, we might even say that the propensity for creativity is part of our Image-bearing-ness. Humans have a creative inclination. However, it wouldn’t be untrue to say that there are people who live more in their creativity, and then some who, through either time or experience, have had that part of them dimmed down. But I am adamant about this, if you are human, you are creative.

Creativity is hard

Now I don’t want you to get the wrong idea, we are all inbuilt with creativity, but creativity isn’t an easy sort of thing, in fact it is hard. It’s hard in the way being a gardener is hard. You till the soil, ready some things, make preparations, and set the groundwork, before anything exciting happens. It can be pretty un-inspiring. This is where most people lose passion. You have to learn the guitar chords before you can write a song, you have to learn how oil paints work before you can capture a scene. This is the groundwork, the unseen. It is the discipline and structure that is set up so that you can be free, free to create. But you can’t be free right out of the gate, otherwise you’ll be free to waste your ideas on poor execution. Your ideas deserve more than that. It is sort of like the difference between the hedonistic and the heroic paths. Without discipline you’ll chase the immediate pleasures of making things for the sake of making them. But if you might choose the other way, and in so doing delay gratification, you might find something truly amazing on the other side of the struggle. You might trade out an unproductive, sad, tomato plant for a whole garden, to keep with the metaphor. But it takes time, and the embracing of the unseen groundwork.

Creativity is about saying something

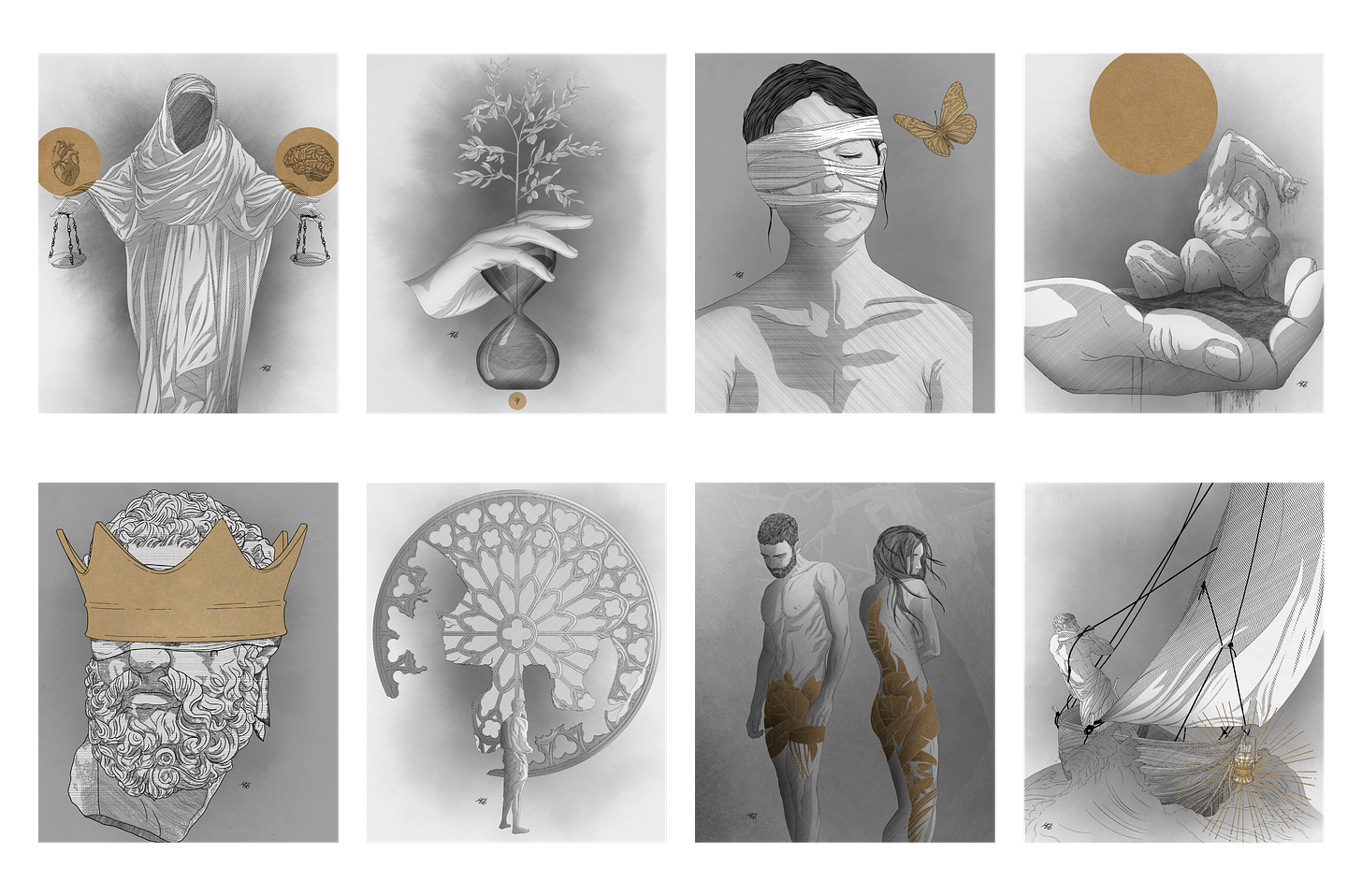

This point might receive some pushback, but I think overall it is true. If you have nothing to say, you’ll end up creating that way. Some people may say that to create is the very act of speaking through the piece itself, but, you still need to have something to say at the beginning, otherwise you may end up in the visual equivalent of babbling on in conversation. But it isn’t always clear what to say is it? Here I’ll use another metaphor. I have found that when I create the best, I treat the whole exercise like a conversation. And in a conversation I might have with a friend, there is a 3 stage movement that happens. I need to receive something, have something said to me, then, I need to collect my thoughts, all before I have the ability to say what I want to say. It isn’t that different with creativity. To put it another way—I need to receive (or at least go looking) for inspiration, sit with that stuff, organize it, and then say something with it. The form this normally takes within my own process is twofold. I really enjoy looking at art, art of all sorts, that is the first one, and it’s pretty simple. If you don’t have any museums you love right around you, you would be surprised how many art museums have images of exhibits online, or how many fine-art apps you can download for your TV to just view art even in your living room. So I try to immerse myself in good art—new and classical artists—to really look at, really see, and try to engage them visually, dissecting what they are trying to do. My other intake is to read. I try to read good books, with good robust thoughts, and then let those thoughts just simmer. Excuse all the mixed metaphors, but you get the idea hopefully. Then, between these two methods, I am sort of stirring my imagination in two ways: sensorially, and thoughtfully. From there I find I have better things to say, and new ways to say them. Before we move on though, I need to say this. To ‘say something’ in creative forms doesn’t have to be the same as saying something articulately. Sometimes the things we want to say cannot really be matched with words—they are different to that, perhaps like a kind of feeling, but, and I want to stress this, that doesn’t mean they are the same thing as having, ‘nothing to say.’

Creativity as a Delta

Sometimes when I speak to folks who are making creativity their life, and from it their livelihood, they express that sometimes they are frustrated about ‘selling-out’ as a creative person by taking contracts or clients that they are not passionate about. Similarly, I have also spoken to folks who want to make creativity their full time job, but they never get it past being in the ‘passion’ phase. This might be where creative-realism is helpful. We might think creativity is sort of like a river, it has a source (the person creating) and an outlet (the exhibit, audience, or perhaps little notebook that the person has access to). However if you look at some of the greatest artists that come to mind: Monet, Renoir, Da Vinci, or Michelangelo, they all did commissioned patron or client work. This, though, didn’t keep them from doing passion projects—just the opposite, it kept them able to do them. It also didn’t mean that they neglected bringing their passions, thoughts, and inspirations to bear on the projects. Their creativity was still a river, but it would work itself out in different ways for different occasions and directions. If that is akin to selling out, then the hard reality is that this will keep creativity in the realm of the abstraction. Sometimes you have to keep the lights on in order to paint by them. I made the decision a long time ago that I would rather create things that occasionally I didn’t love, in order to make the space for me to create things I did. And to my surprise, I have also found that I have loved projects that I never thought I would at the onset. It all seemed a better arrangement than not creating at all. And it doesn’t mean that you still can’t sow yourself into the work you are not passionate about, nor does it mean you cannot say something important with it, and perhaps in the process of problem solving, a person might become better at creativity, and not worse.

Creativity is worth keeping alive.

Now I want to end with a bigger, kind of ‘purpose’ section. Whether we are talking about the individual or the cultural landscape at large, we need to keep creativity alive. As many of you have probably heard me say a thousand times already, we are at a crossroads. As Artificial Intelligence is coming on-line we can already see something worrying. We didn’t give it the menial jobs alone like we were promised, in fact we gave it our greatest goods right out of the gate. Our art. The proliferation of AI art will pose larger and larger problems in the future (I wrote an entire article over the summer concerning AI art, you can find it here). But that is only a symptom of an older, larger problem. We see another symptom of it in what we call ‘content,’ and the encouragement of a dizzying, disorienting amount of loud voices vying for clout and attention. We see it also in how we consume as consumers, and for the producer, how they produce. The real creativity is being traded for expedient facsimile, creators are being either hamstrung or hemmed into cookie-cutter-trend-minimalism. To tie all of these strands together, we might state the base problem like this: we are losing our ability to sit around our village fires and tell stories. Stories that are more than bare-bones, they are personal, they are part of us. Stories that are artful, and resist reductionism. We are “meaning seeking animals” as Jonathan Sacks wrote. But we are being caught between two movements, meaninglessness and hyper-consumerism. We despair and so we numb. A terrifying real world realization of Huxley’s Soma. The creatives are being turned into advertisers, or forced to give up in a quiet kind of Darwinian extinction. There has never been a better time to push back against this. Never a better time to become people who slow down, who create, who ponder, who tell stories, and who seek meaning. And it might just mean doing it in the margins of life, to keep the little light lit. This is where the realism comes in again. Perhaps it is pursuing art instead of scrolling, or writing a short thing before bed. Maybe it means being a great story-teller to your kids. This will be one of the chiefest battles of our lives. It really is about our humanity. I agree with Justin Brierley, who echoes Charles Taylor, we need to re-enchant the world. In the end, we are faced with this question: can we keep telling stories around the fire, painting on the rock walls, or will we simply sink into the distraction of modern meaninglessness. I want this to be a call to hope, not despair. There has never been a better time to create, to become artisans, than now, this, an act of subtle resistance.

“The two most influential works of Western modernity – Hobbes’ Leviathan and Adam Smith’s The Wealth of Nations – were predicated on the idea of humans as the maximising animal. Politically this led to the social contract; economically to the division of labour and the free market. Humankind, however, is not merely a maximising animal. We are also, uniquely, the meaning-seeking animal. We seek to understand our place in the universe. We want to know where we have come from, where we are going to, and of what narrative we are a part. We form families, communities and societies. We tell stories, some of which have the status of sacred texts. We perform rituals that dramatise the structure of reality. We have languages, cultures, moralities and faiths. These things are essential to our sense of continuity with the past and responsibility to the future.”

—Jonathan Sacks, The Dignity of Difference