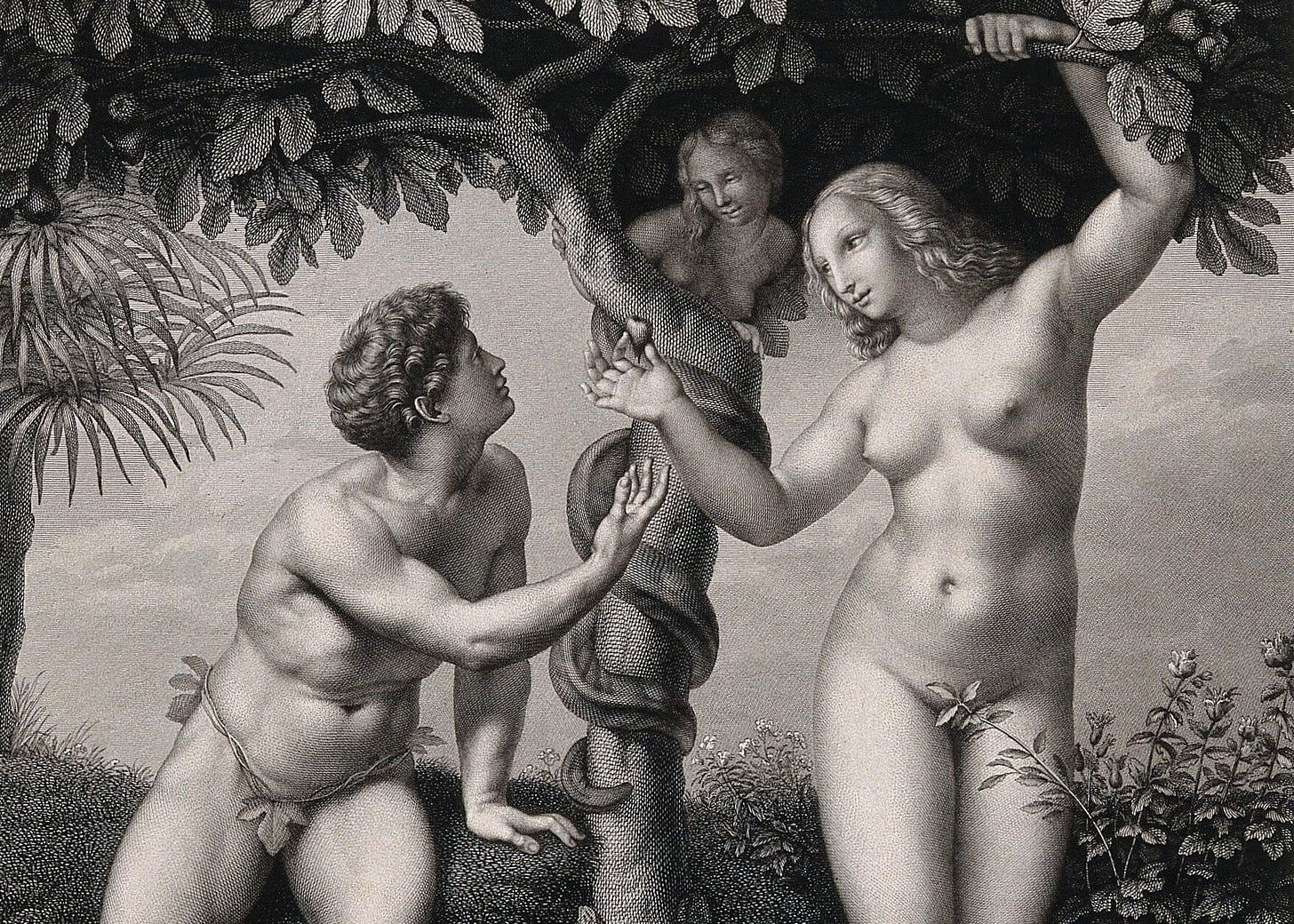

I was working on an illustration this week that centered on Adam and Eve. Reading it, rereading it, it’s a strange story. And I find the more I sit with it, the stranger it gets. It’s weird in a way that looking out your window on a foggy evening is, crepuscule shapes shifting. As soon as you get an idea of the picture you’re looking at, it starts to move in unexpected ways. Yet, the more it is sat with, the less there is a feeling of needing to explain it, in a way, and the more it is felt. The strangeness of the story is the story.

Humans are strange creatures. Always restless. I think it’s funny when people taunt how unrealistic this tale of Eden is. Really? In a story where utopia and everything with it is given to humanity, even bliss of relationship with the highest thing in the whole cosmos, we cannot fathom humans wandering off looking for something else? Perhaps we are more rational than they.

The more I read it, however, the more I think the text knows us better than we know ourselves. Sons of Adam, daughters of Eve, human, the illustrative power is humbling. And our species still wander restless. My wife and I the other night watched a beautifully done documentary on an archeological dig currently happening at a cave in the Middle East. The dig was focused on learning from the funerary goods within this cave burial, discovering their symbolism. But the thing that strikes you as much as anything as you watch this dig unfold, besides the grave, the goods, is the character of the cave itself in the drama. The cave operates under different temporal conditions than the world outside it.

The stalagmites and stalactites are built in millenniums. They are cathedrals made not in time, but from time. And so to consider this burial in the cave is to consider its engagement with time, both inside the cave, and also outside of it. Buried 75,000 years ago would mean the occupant would have lived a full 24,000 years before the oldest representative cave art ever to have been found would have been created. This yawning gulf of time is something we struggle to even hold on to. The mind swims in the numbers.

Inside the cave, the burial lay. And the years passed, year upon year, and outside the cave carvings gave way to language, language led to culture, and culture grew and developed, changed and morphed, only to change the face of the planet outside the cave itself. The first ochre paintings would lead to microchips while the cave grew its naves and buttresses, and the grave would remain occupied while hunters and gatherers gave way to astronauts.

Yet one thing remained still. All the time outside, humans searched on. Perhaps that is the curse of humanity, the truth of the curse: always searching but never finding, “always learning and never able to arrive at a knowledge of the truth.”1 The target has become more ambitious all the time: to leave one’s valley for another, to go across the sea, to set foot on another planet. And yet it occurs to me that we have left Eden and done our best to forget it—but the search fails to satisfy, and the God we left behind waits. Waits longer than the cave.2 Waiting for the cleverness to give way to realization, for hurriedness to give way to a stilling.

It is obvious enough that humans have the yearning for exploration, this a byproduct of our desire for knowledge. And yet, where we might go is not too far from the God who desires us to dwell with him, indeed it would make good sense that as we engage this creation, exploration is not the problem, nor the hunt for knowledge, as “The earth is the LORD’s and the fullness thereof, the world and those who dwell therein.”3 But perhaps it is that we have settled for wanting to be heroes of exploration when all along we were meant to be well taught sons and daughters.

Consider our new pursuit. We in the last few years, have been straining at the bit to discover life on other planets, but why? I mean this question ontologically, what would it meant to us (and about us) if we found other life, existentially? We search for alien life, perhaps, because we long to find other minds, other minds that we might connect with, minds that are not us—but might help us make sense of who we are. It is, in essence, an existential pursuit, built on the back of the famous question—‘are we alone?’

Might all of this be the energy of searching—knowing there is something to be found, or perhaps better put, something that has been lost, that we long to refind? There are some people who dream of finding alien micro-organisms, bacteria—but there are whole cultural industries built on the idea of first contact: communication. We don’t want to just find life, we want to find sentient life. We don’t want to just find other minds, we want to communicate with them, and in the process, make sense of ourselves.

We seem prodigally restless—this notion may take some time to sit with. Now, if we are prone to restlessness, what does the voice of Christianity lend to the conversation? I think it might say, ‘yes engage the world, explore the world, but remember the cave.’ In the cave we remember that we are both small and short lived. In the cave we remember that all the cleverness is reduced inconveniently to very little: in the words of Kohelet, just temporal vapor, here now, but soon gone. For all of our cleverness outside the cave, there is a grave still in it.

And so it seems if what we know as reality is real, then unfortunately we have some grappling to do. And so, by our cleverness we have both alluded some ignorance and also, for a time, some of ourselves. Our knowledge cannot save us from reality. And this is the force of the story of Eden. It is an inverted hero’s journey: to come home is to engage truth, the more-ness of supernaturality, and the salvation—not to mention, restoration, of the original relationship.

This sprawling story of the first Adam to the second Adam (Christ) seems nothing short of us being called, beckoned, by a father waiting for his prodigal wanderer to return. And yet it goes deeper than that, the prodigal returns not to restriction but to knowledge “as the water covers the sea,”4 only to find that all that restlessness we possessed was set within our post-edenic dimmed senses, our darkened mirror.5 We were called to something else though, we were called back that we might finally see, finally know. In the end, we might very well find that before the divine breath fell upon the dust of Genesis, and humanity rose from it, the Creator God knew that this dust would take Him and bury him—the cost of their being made, and their being made free. And in this way, one cave would set free all others, graves emptied. The Creator would descend to raise those dust creatures with Him.

And so we are beckoned to, urged against our frantic chase, against our hurried cleverness, that we may be still and know.6 Know the God waiting for us. Sons and daughters of Adam, Eve, brothers and sisters to Pilate—beckoned to by a God who has been waiting all this time, calling unto us all this time, going into the cave, all for us to ask, “What is truth?”7 and mean it.

2 Timothy 3.7

Job 38.4-6

Psalm 24.1

Habakkuk 2.15

1 Corinthians 13.12

Psalm 46.10

John 18.38

Thank you Seth.